What is Earth System Data Science?

The purpose of this site is to provide some insights into how to do common data science tasks in the context of earth system science (ESS). Generally speaking, earth system science focuses on interactions between the various “spheres” of the earth system. In the context of this site, we’re largely going to focus on the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and pedosphere (Soils! Please don’t put me on some kind of FBI list…), with some of the biosphere thrown in for good measure.

Data science (DS), like ESS, is also multi-disciplinary, and includes concepts from statistics, computer science, programming, etc. Thus, the combination of ESS and DS is earth system data science (ESDS). In this context, we’ll be moving through a number a techniques and algorithms that can be used in ESDS to answer questions we might have about the Earth system. These could include:

- How well do predicted mean annual air temperatures describe observed air temperatures at weather stations?

- Has river discharge changed across the US over the last century, and do those shifts express a spatial pattern?

- Are there “natural” flow regimes across rivers in the US?

- How do soil physical, hydrological, and chemical properties influence each other?

- Can we classify a wetland based on landscape features (e.g., elevation, imagery)?

We’ll touch on some of the above questions, plus some others, using differing data science techniques that range, loosely, from regression to classification.

Core data science algorithms

There are a HUGE number of data science techniques out there. Too many for a single website. So, instead of doing all of them, we are just going to focus on a few really common ones. Loosely, DS and statistical techniques can be broken up into two broad categories that are not mutually exclusive, nor exhaustive: regression and classification.

Regression

Regression principally focuses on numerical outputs. If you think back to your statistics 101 class (or at least that’s when I learned about data types), there are two broad ranges of data: numerical and categorical. Categorical data can be split into nominal and ordinal types, while numerical data consists of interval and ratio data. It is ratio data that regression is largely focused on.

Classification

Classification tends to focus on categorical outputs, which tend to be more in the realm of nominal, ordinal, and sometimes interval data types. Arguably, classification is the more common and difficult problem in data science, compared to regression, and comes in two “flavors”: unsupervised and supervised.

Unsupervised classification is great for understanding relationships between groups, especially if the number of groups is already known and the boundaries between those groups are pretty obvious (mathematically speaking).

A major problem in classification, however, is that the boundaries of a class may be “fuzzy”. For example, where do mountains end? That is, if we wanted to discretize pixels in a raster to “mountain” vs “non-mountain”, what criteria and data would we provide a given classification algorithm to generate those two classes? Elevation? Slope? At what scale?

To help with the “fuzzy” problem, where groups do not obviously distinguish themselves from one another, we have supervised classification. As the name suggests, we include human supervision to help “train” an algorithm to properly classify data.

And everything else

The above dichotomies are somewhat artificial, however. For example, is multinomial logistic regression a regression or classification algorithm? It has elements of regression (as the name suggests), but is often used for classification problems. Thus, we might see regression and classification as end-members rather than as mutually exclusive categories.

However, even the end-member construct may be artificial, as there are other problems that don’t fit cleanly between the ideas of regression and classification. For example, where does structural equation modeling fit in all this? Probably closer to regression, but not exactly. What about principle component analysis or non-metric multi-dimensional scaling?

The techniques covered used in this site

Based on the above perspectives, the site is grouped into three categories: regression, classification, and everything else. Using those categories, we are going to “interrogate” different data sets to see how the different algorithms might help as answer questions relevant to ESS. Full explanations of how the algorithms work are beyond the scope of this site. Instead, I’m hoping what I’ve done will motivate you to look into the underlying math yourself (and maybe even buy a linear algebra book, which is pretty fundamental to a lot of these problems).

Regression

- Comparison (A/B testing)

- T-test

- Mann-Whitney test

- Prediction

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- Linear regression

- Multilinear regression

- Hierarchical regression

- Generalized linear models (GLMs)

- Logistic regression

- Generalized additive models (GAMs)

- Non-linear optimization

- Hierarchical non-linear modeling

Classification

- Unsupervised

- k-nearest neighbor (kNN)

- k-means clustering

- Supervised

- Discriminant analysis

- Naive Bayesian classification

- Classification and regression trees (CART)

- Random forests

- Neural networks

- Deep neural networks

Everything else

- Dimensionality reduction

- Principle component analysis (PCA)

- Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS)

- Gradient boosting

- Collaborative filtering

- Structural equation modeling

- Path analysis

- Time series analysis

- Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA)

- Uncertainty assessment

- Leave-one-out cross validation

- K-folds cross validation

Frequentist vs Bayesian paradigms

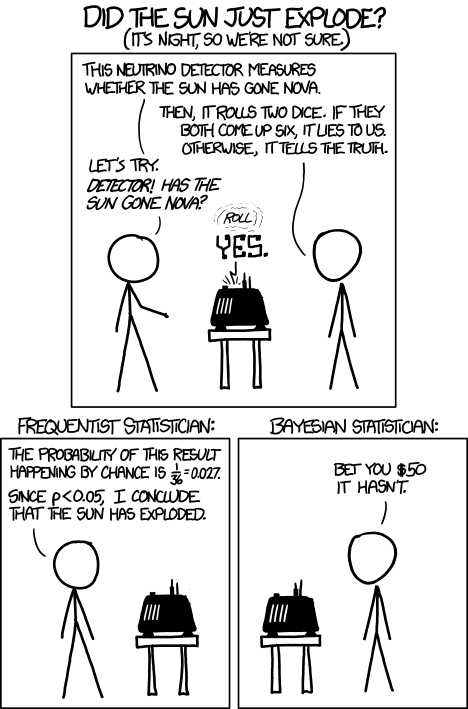

In statistics, there are two major paradigms: Frequentism and Bayesianism. A thorough review of these two schools of thought is beyond the scope of this site, but see the “General resources” section for other places where such reviews have been made. However, the two ideas are pretty well summarized by the following (XKCD):

In essence, the Bayesian view point allows us to incorporate past information, if it exists, to update our understanding of how a system works and our confidence in our new understanding. In the context of the comic above, this means we can incorporate past experience related to the sun (not) exploding to better predict if a model’s results are anomalous.

In practice, this tends to produce greater model uncertainties than Frequentist methods, meaning we are being conservative with how well we think a model will predict some condition of interest. At first that may sound bad, as we want precise predictions, but I’ll argue that this model conservatism is a good thing, because it doesn’t promote as much over confidence in results.

Bayesian techniques are particularly powerful when:

- One has limited data.

- There is prior information about a system (or similar system) of interest.

- A model is complex.

The downside is that Bayesian techniques tend to be more computational expensive (they use Markov Chain Monte Carlo to solve relatively intractable integrals) and can be pretty sensitive to priors, depending on how they are implemented.

Last, while Frequentism and Bayesianism are often thought of as being antagonistic, I think that perspective is somewhat counter productive. This is particularly true in cases antithetical to the (numbered) use cases listed above, as the two paradigms will tend to converge on the same solution, thus reducing the complexity of analysis often required for Bayesian analysis.

Approach we’ll be using

We’ll largely use a Frequentist approach, because the tools for Frequentist analysis are much more abundant and developed. That said, I will also sometimes include Bayesian assessments of probability. Specifically, I will be using Stan, which is a statistical programming language for Bayesian analysis and integrates with a number of other languages including R and Python.

Programming and reproducibility

I’m going to focus on using the R statistical programming language, because it has become a favorite generalist scripting language used in the statistics, biology, and ESS communities. It is also highly extensible and was used to build this website via the knitr and rmarkdown packages.

In the context of R, I’ll be largely following “tidyverse” principles related to formating code and data. The Tidyverse Style Guide has more on generating tidy code. Chapter 12 of R for Data Science has more on tidy data.

Also, all files and code used to generate this site are available at: https://github.com/wetlandscapes/esds